Creating Immediacy

I'm filled with a constant sense of urgency right now. Each day I feel a little more of my time burning away from me.

There is no guaranteed tomorrow so I want to do what I love today: making lots of things. Recently I've been using my spare time to build a modbile app, a quantum measurement apparatus, philosophical conjectures, and irrigation systems. In this post, I wanted to share how I built the Immediacy App. It turns out building Android apps is pretty confusing and also pretty cool.

If you're interested in the development process, I've tried to lay out the details below. This is mostly a reference for me, but might contain a useful jump-start for anyone looking to do something similar.

Using Firebase

To build the app, I relied heavily on a free Google Cloud platform called Firebase, which serves as an all-in-one real-time NoSQL database with simple APIs to query the database. Using it kept me from having to manage my own server or the database for storage (ops scares me). And more importantly, it has a very generous free usage tier, which should easily cover the handful of people I expect to ever use this thing.

To learn how to use Firebase, I followed along with this chat app tutorial. This covers the setup of a project and connecting it to some Android sample code for a chat app.

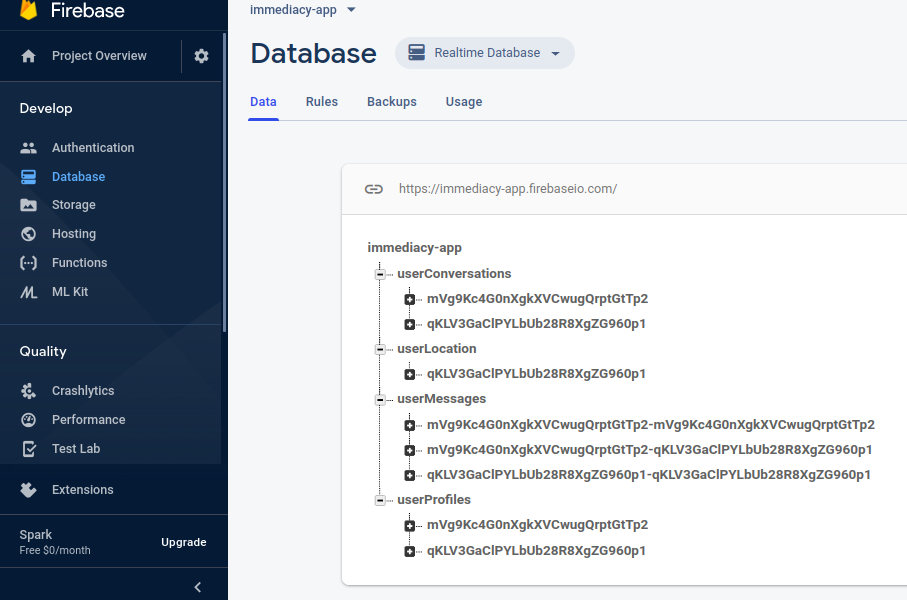

Mostly Firebase is just a fast way to store and retrieve data. The data structure just looks like a nested tree (like json) with a bunch of nonsensical keys used to identify whatever object is interesting.

As you can see the database has 4 keys where it stores the users' profiles, conversations, messages and locations. Generally, you call this database with Firebase specific access functions (see below) to traverse the tree and get all the relevant data. Firebase also lets you expand the nodes of the tree to dig down into the data right through their UI, which is pretty convenient.

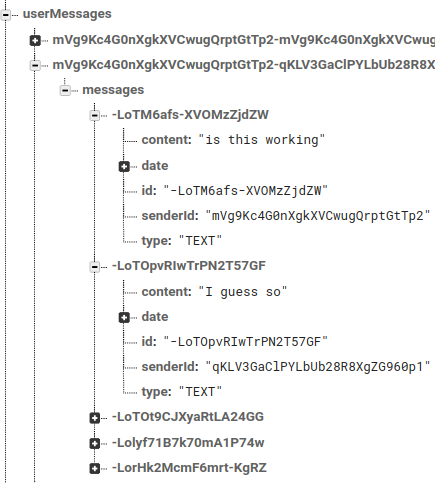

Here we can see how a few test messages were stored. Under the userMessages node are all the pairs of users who have had messages. Then under that there is a node to denote the messages. That node houses a list of messages, complete with sender and content.

One particularly great thing that Firebase does is keep track of all the users on the site and provide login protocols for authenticating them. Having bona fide User objects makes it much easier to access user specific data throughout the application.

With a Firebase database setup and Authentication taken care of, the next step is to get some code to run the Android app on a phone.

Android Programming

One of the keys to getting shit done in software development these days is to borrow heavily from open-source projects. Or to put it another way, this project started with browsing Github for a couple of hours to find someone else's project to steal outright.

Nearby-Chat

With a basic understanding of Firebase, I started perusing for open-source Android apps that related to what I was trying to make. I started working with a Github project called Lets-Chat, and I adapted it to get something that worked for creating direct messages. Unfortunately, it didn't have anything related to location built-in. Instead of building that from scratch, I found another promising example called Frinder, but that one turned out to be mostly just a mockup that didn't quite work right.

Finally, I stumbled on a project by Sandu Postaru called Nearby-Chat that looked almost exactly like what I was looking for. It used an add-on to Firebase called GeoFire, along with Google Maps API to display the location of nearby people to chat with.

This was great because it basically did everything I needed to do. The only downside was that it actually revealed the nearby users' exact location to everybody, which I thought was a little creepy. Fortunately, this meant that all I had to do was remove some functionality and tweak the "Users List" to only include people who were very close.

The Components of the Mobile App

Android programming is super confusing to me, and I have only scratched the surface of it. In this section, I'm really just jotting introductory notes for myself on the different parts of an Android program. If you don't get Android this section might help explain things, but I'm also likely to be incorrect about some stuff in here. Follow at your own risk.

Activities and Fragments

In Android parlance, the different main pages of the app are called "Activities." When there are subsections in a single activity, there are segments called Fragments. In Nearby-Chat, there were four activities:

- MainActivity: activity launched on startup

- OnlineActivity: activity launched after user has logged in

- ProfileActivity: separate activity for editing user's profile

- ChatActivity: separate activity for an individual chat session

The MainActivity had two fragments, one for registering new users and one for logging in. I left both of those untouched. The OnlineActivity also had two fragments: the MapFragment which held the map with nearby users, and the ConversationsFragment, which held a list of all the conversations that were currently ongoing.

To convert Nearby-Chat into Immediacy, I needed to replace the MapFragment with a NearbyListFragment, which just presented a list of users were close by. Fortunately, the code already had a place in it (OnlineUsersAdapter) that rendered a page that showed the full list of users. So all I needed to do was combine the filtering and fetching of users from the MapFragment with the list functionality of OnlineUsersAdapter.

Adapters?

I mentioned Activities and Fragments, but there is another part in Android programming called an Adapter that wasn't clear to me at first. My interpretation is that all your data will come back one item at a time and the adapter is just a way to connect that data to the actual UI. All of th adapters I was working with were extensions of ArrayAdapter, which meant that I was going to get lists of items and convert them into lists of objects in the UI in some way. The way this happens is by adding Callbacks and Listeners

Callbacks and Listeners

The big thing that's always been hard for me to understand about both web and mobile apps these days is the idea of callbacks and listeners. Programming with callbacks means almost none of your code gets called directly by the program when it starts up. Instead on startup you just set the functions to listen for events, and those events then call all these interrelated functions that each trigger each other. It makes sense because you want many things to happen potentially at once, but you still need some way to orchestrate subprocesses to happen after all the things that need to happen first happen. But it still means things are a little confusing—at least to me.

For my NearbyListFragment, I added a locationCallback function, and set up the fragment to listen for the user's location.

activity = (NearbyListFragment.OnFragmentInteractionListener) context;

activity.addLocationCallback(locationCallback);

When the phone retrieves the location from the device's GPS it send it to my callback's "onLocationResult" function.

private final LocationCallback locationCallback = new LocationCallback() {

public void onLocationResult(LocationResult locationResult) {

for (Location location : locationResult.getLocations()) {

GeoLocation myLocation = new GeoLocation(location.getLatitude(), location.getLongitude());

geoFire.setLocation(userId, myLocation);

geoQuery = geoFire.queryAtLocation(myLocation, RADIUS);

geoQuery.addGeoQueryEventListener(geoQueryEventListener);

...

This code first sends the location to the geoFire database and then sets up a query based on the current location and the search radius. On the Firebase side, geoFire.queryAtLocation is set up to look for other locations that are within the given RADIUS. Finally, I add a geoQueryEventListener to wait for geoFire to send a location based event back. The code for the GeoQueryEventListener takes this whole "Listener" thing to a new level.

private final GeoQueryEventListener geoQueryEventListener = new GeoQueryEventListener() {

public void onKeyEntered(String key, GeoLocation location) {

LatLng latLng = new LatLng(location.latitude, location.longitude);

DatabaseUtils.getUserProfileReferenceById(key).addListenerForSingleValueEvent(new ValueEventListener() {

public void onDataChange(DataSnapshot dataSnapshot) {

UserProfile userProfile = dataSnapshot.getValue(UserProfile.class);

onlineUsersAdapter.add(userProfile);

...

This creates a listener that will wait to run its functions whenever the Firebase database registers an event. Specifically, whenever there is a "KeyEntered" event (ie someone enters within a predefined distance from the user), the onKeyEntered" function will be called. This then generates yet another "ValueEventListener," which waits for the database to return the data associated with the "KeyEntered" event (ie the UseProfile information for the user that entered the area).

At this point, the new user is added to the "OnlineUsersAdapter." As mentioned above this adapter is an ArrayAdapter so for every user in the list, a view is created, which sets the values for the user_name, user_bio, and user_avatar.

public View getView(int position, @Nullable View convertView, @NonNull ViewGroup parent){

final UserProfile user = userProfileList.get(position);

TextView userName = (TextView) convertView.findViewById(R.id.active_user_name);

TextView userBio = (TextView) convertView.findViewById(R.id.active_user_bio);

ImageView userAvatar = (ImageView) convertView.findViewById(R.id.active_user_avatar);

userName.setText(user.getUserName());

userBio.setText(user.getBio());

userAvatar.setImageBitmap(user.getAvatar());

The advantage of all of this is that almost all of the work is done by the Firebase server, and your mobile app doesn't really spend any wasted time waiting for data to come back. It just sets up an event listener or a callback and then comes back to life when the event occurs. It's kind of all magic to me.

Models

The last thing to mention is that all of the data stored in Firebase was basically used to construct Java Objects. The details about these Objects and what variables were associated with them was always stored in the models/ directory. There were model objects for Conversation, Message, OnlineUser, UserConversations, UserMessages, UserProfile.

The way to then reload these objects from Firebase is by passing the Firebase object the java object's class. As an example, in the above code, I regenerated a UserProfile using the data in the "dataSnapshot" by passing it the UserProfile.class.

UserProfile userProfile = dataSnapshot.getValue(UserProfile.class);

Putting it all together

A crucial step in all of this is getting the code onto a device where you can test it. Fortunately, you can follow these instructions to set up an Android device for connecting to Android Studio on a Linux machine.

The Android Studio interface is pretty painful to work with, but it allows you to render your UI components and performs all the code linking for you.

Admittedly, Android Studio does a ton of package management that I truly don't understand. Something called gradle is always building things in the background and reorganizing files, and it leaves me feeling totally lost. Honestly, I spent one whole night (probably 4 hours) just trying to get Gradle working again. All it told me was "Input/output error" without any other context. For the record, I eventually figured out I had to delete my ~/.gradle folder. I kind of hate Android programming because it uses such a clunky and black-box tool to generate the entire build process.

But long story short, the thing gets compiled and pushed over to my phone where I can play with it.

Deployment

For the final step, I wanted people to actually be able to use this thing. So I plan on spending the cash ($25! wtf) for a developer license, so I can upload my app onto the Google Play store. When I get that finished I'll update here a link and how to

will stedden

will stedden