Making Better Eyes

Epistemic status: Currently engaging in exploratory experiments to determine validity of hypothesis. 10% confidence of success, but experiment is low risk, which makes it worth pursuing.

In May 2017, I had an eye exam with my new optometrist. During that visit, my optometrist made a passing remark about a quirk that he noticed in my old glasses. That tiny remark completely changed my perspective on optometry and near-sightedness. And I'm hoping that it might just change my life.

Why had I never thought of that before?

All this started when my new optometrist asked me nonchalantly whether my previous optometrist had ever mentioned putting a prism in my glasses. I'm severely myopic (or near-sighted) with a prescription of around -7.5 diopters in my glasses. This means I need to take my prescriptions pretty seriously because getting the wrong glasses means I can't see much farther than 12 inches in front of me.

Now, as it just so happened, I had taken my prior prescription to the online eyeglasses retailer, Warby Parker, so I knew very well that there was no mention of "prism" anywhere on my prescription. Moreover, even though I've been going to the optometrist for more than 20 years, I had never heard about prism before. Since I didn't know what prism was, I asked what it meant for glasses to have prism.Essentially, as my doctor explained, prism means that the center of the focus of the lens is not aligned with the center of your eye. In other words, it means the lens of the glasses are offset. This is normally done intentionally when a person has a misaligned eye that needs to be corrected. But since I knew that my old prescription didn't mention prism, I told the optometrist that it must have been a mistake, and that I remember having a really hard time adjusting to my glasses when I got them. And then he responded with a statement that completely took me by surprise.

It must have just been lucky then because you actually need exactly the same amount of prism that is in your glasses.

I could tell by the way that he said it that he wasn't questioning the arrow of causation, but to me, the following painfully obvious question instantly sprung loose in my imagination:

Could my new-found prism have been caused by my glasses?

Knowing what little I knew about biology, it seemed more likely to me that my eye would have adapted to an erroneous prism than that the accidental prism and the never before diagnosed prism happened to just perfectly counterbalance. So if I assume that my glasses were able to retrain my eye to adjust for a prism, it isn't too difficult to jump to the next obvious question:

Could other vision problems be induced by glasses, specifically, my progressive myopia?

I was floored. How had that thought never occurred to me? I feel pretty stupid for never thinking about it, but once the idea was in my head, I had to get an answer.

What causes myopia?

To explain why I'd never thought of this before, we have to understand my previously correct yet limited understanding of the cause of myopia. In short, myopia is caused by the lens of the eye being unable to properly focus a distant image on the retina of the eye. If we look at a picture of light coming into a simple convex lens (like the one in our eye), we would see all the light being redirected to focus down to a single point, called the focal point.

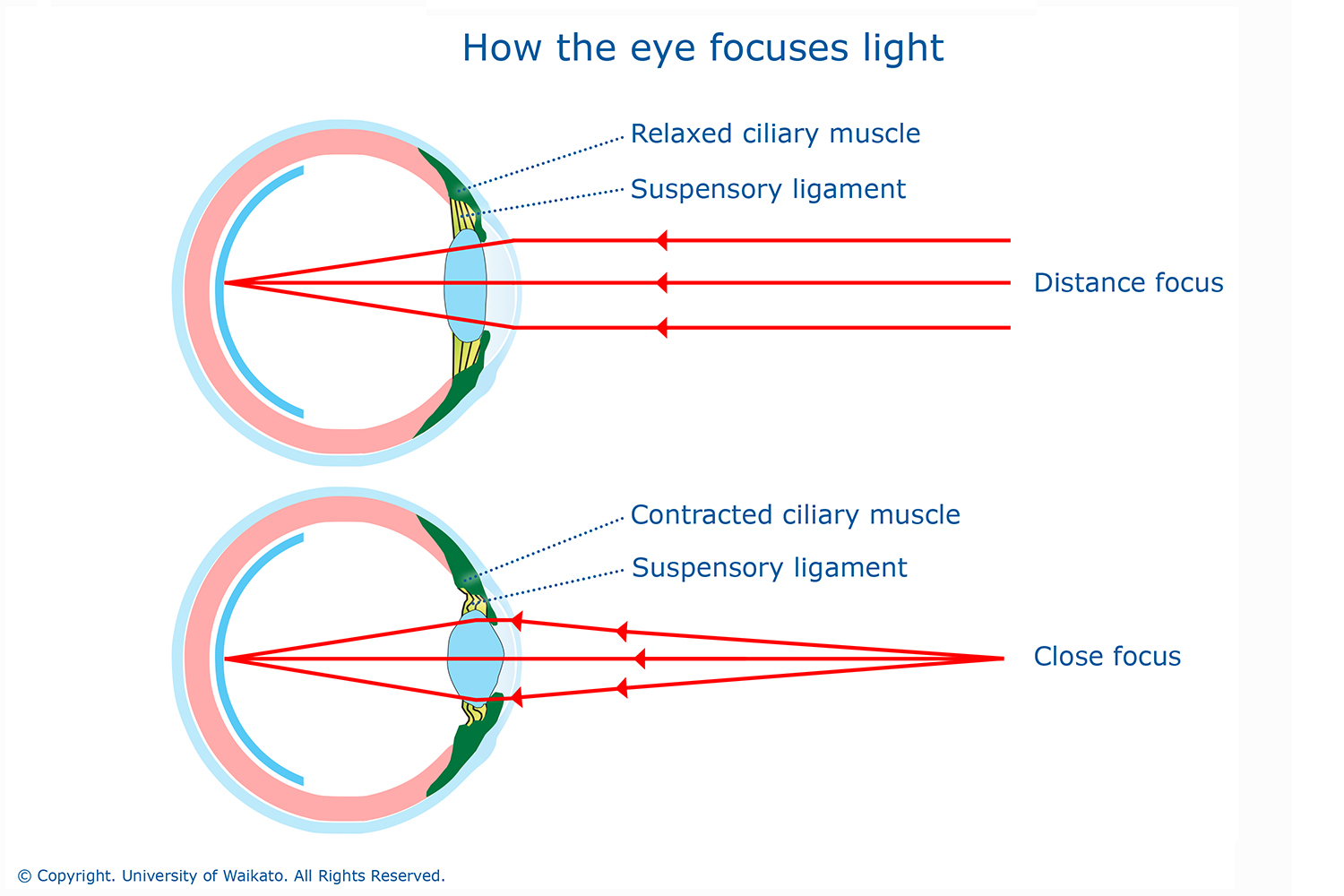

The exact shape of the lens determines how much the light rays are redirected, which sets the focal length or how far away the focal point occurs. This occurs in a camera, a telescope, and most importantly our eyes. In our eyes, this means that light coming from an object will focus down to a little miniature image at the focal point on the other side of our lens. Basically, if you want the mini image to always appear at the same location (your retina), but the real object is at a different location, you will need a different thickness of lens. The eye provides this ability by giving us muscles that quite literally squeeze our lens to change its thickness.

The problem with myopia is just that the lens in your eye can't get thin enough to turn a far away object into an image at the exact location of your retina. Instead, the image is focused a little bit in front of the back of the retina, which causes the image at the retina to be fuzzy. The underlying reason can either be due to the lens being too thick or from the eyeball being too elongated.

Either way, you should note that myopia doesn't come from an inability of your muscle to squeeze the lens hard enough, but, rather, a failure of the muscle to release the lens far enough. The corrective lens actually is making up for a mismatch between the minimum thickness of your lens and the elongation of the eyeball.

Most people with a technical degree will be introduced to this information around their freshmen or junior year of college. Since I felt like I knew a little about optics, I felt like I perfectly understood the problem. However, this still leaves the question of why some eyes are able to stay functional, while others come out of alignment.

The mechanics of short-sightedness

The next question one has to ask is Why is a myopic person's eyeball elongated?

I'd heard that the cause for the misalignment was genetic, due to some deficiency in the formation of the eye. The explanation that I remember hearing from my early optometrists only informed me that my eye was somehow too elongated. This is true relative to the minimum thickness of my lens, since my eye is literally too elongated for even my most relaxed focal point to reach it. This means that there is nothing I can do to get that focal point to my retina because any amount that I squish my lens to get thicker only moves the point of focus further toward the center of the eye and away from my retina at the back.

Although my optometrists accurately explained this immediate cause of my failure to focus, they never went into specifics of how my eye got to be that way, only suggesting that I had a genetic problem. But I can remember thinking how strange it was that so many people could be so blind so suddenly if this was an underlying genetic problem. About 30% of people in the United States are near-sighted today so, logically, then shouldn't approximately 30% of people have needed glasses 200 years ago too? That's just how genetics work. But 200 years ago glasses were a rare luxury for the rich so 30% of the country would have been effectively blind! At the time, I explained it away to myself by saying, "Well my grandparents were all farmers; maybe on the farm no one noticed that they were going blind."

The biological case for vision adaptation

As far as I know, no one can state for sure what is truly the causing the sudden epidemic of progressive myopia. In 2015, the journal Nature posted this article, suggesting that the myopia boom was due to children not being exposed to enough sunlight. The evidence they cite (pun intended) is that children who spend more time outside tend to have lower levels of myopia.

However, a more parsimonious explanation, and one that is more widely accepted than the outdoor light theory, is simply that being outside means you are spending more time focusing on things that are far away. Being inside probably means you are looking at nearby objects, like books or computers more often. In short, it's possible that myopia is nothing more than the eye trying to adapt to the environment it is put into day after day.

There are many hundreds of complex feedback mechanisms that our bodies have in place, tuning our various physiological processes to fall into homoeostasis (here's a tiny handful of examples). From our kidneys nearly instantly setting the osmolarity, pH or ion concentration of our blood, to our muscles slowly adapting to the toll of the labor, to the development of the size of our fingers and toes, the body almost magically tunes itself to function properly. Why should vision be any different?

I'm not alone in my belief that myopia is really just an adaptation to keeping the eye focused close up. Many research studies in animals and on many different populations suggest that close work is a plausible cause of myopia, and that close-up focus along with genetic factors is what is causing the increase in myopia today. I don't have time to enumerate all the details of these studies, but if you'd like a high level overview of the research, I suggest you listen to the first half of this excellent talk by Todd Becker.

The glasses problem

Of course, the issue isn't just that there are more myopic people. The issue is really that there are so many more people with an advanced level of myopia. In fact, the levels of severe myopia are measurably higher among young people than they are among the elderly. This leads to the question about what could be causing the pandemic worsening degree of myopia, and to one conclusion: that our increased reliance on glasses is making myopia worse.

This point is more controversial than the issue of near-work causing myopia. However, it is very clear that myopia can be intentionally induced in animals through the use of corrective lenses. In these studies, scientists put a pair of glasses onto chickens who presumably have pretty good eyesight.

They wait a while and then measure the chicken's eyes and find, lo and behold, that the chicken with glasses have a much longer eyeball. In short, the chicken's that wore glasses are now myopic even thought their peers without glasses are still just fine. Recently, researchers have proposed the incremental retinal defocus theory as a way to explain this phenomenon, which basically suggests that defocus releases chemicals that affect eye growth. If the same effect works in humans (and why shouldn't it), this would explain why people with glasses end up needing a higher prescription later on.

On the other hand, I find it hard to believe that something this obvious wouldn't have been noticed and addressed a long time ago. If glasses were so obviously making us go blind, why wouldn't we have enacted measures to reduce our dependence on them. In fact, there have been several studies that dissuade me from believing in the validity of this mechanism. For starters, several studies have shown that undercorrection of myopia can lead to worsening myopia in youth and adolescents (though counteracting the effects of near work with plus lenses has been shown to prevent myopia progression). And it appears that there are probably genetic factors that increase one's susceptibility to near work causing myopia.

Is bad vision correctable?

All of this is well and good if it can be shown that developing eyes are harmed by the introduction of glasses. However, that doesn't do me much good other than showing me that I should keep my kids as far away from the optometrist as possible. The big question I need to answer is if there is anything that I can do today to undo the harm that may have occurred thanks to a misguided public health policy.

I still do not know if vision is correctable through training. It's very clear from published research that adult and juvenile eyes will respond adaptively to stimuli. In addition, there are many, many groups and blogs online that swear they have been able to achieve improvements in eyesight through various regimens. However, conventional optometrists don't acknowledge any of this as even borderline legitimate. I admit my ignorance on this subject, but I also admit I'm more than a little optimistic that I'll soon find out.

An experiment in vision correction

Before I bought new glasses I decided I wanted to see if I could start to push my vision back in the direction of 20/20. I figure there isn't that much to lose: My vision is already so bad that LASIK is a dangerous bet, Ortho-K isn't possible, contact lenses will continue to leave me with dry, fatigued eyes by sundown, and my increasingly heavy glasses will forever limit my ability to maintain an active, healthy life. At -7.5 diopters, I'm on the road to blindness if I don't do something.

Trying to be scientific

I'm not the best scientist, but that doesn't mean I don't want to try to be as systematic as possible in my approach to improving my eyesight. Towards that goal, I'm writing this blog post for a couple of reasons. First, I want to make sure I had a relatively decent understanding of the basic science that underpins the justification for the possibility of vision correction. Writing a post always makes me double check my research so I don't say something stupid. But beyond this, I want to document in a reasonably reproducible manner the approach I'm taking to improve my vision. I want to make it clear what I'm trying to do up front, and then, after a few years, I can fairly evaluate whether I've seen any improvement and what led to such improvement.

Stating the goal and the methods before the study is a valuable approach in Open Science for two reasons. First, if I am successful, after the fact there can be no accusation that I fudged something or that I misrepresented my approach. On the other hand, if it doesn't work, I will have a record that I tried and failed. If everyone records their failed attempts too, then we'll start to get some grassroots confirmation that this really isn't possible. There's always the possibility that the field of optometry isn't deluding us, and I would like to reveal in an unbiased way what proof my experience can offer.

My experimental technique

Although many different forms of vision remedy exist on the internet (and some are just plain quackery), I've tried to pick a very simple routine.

- When doing all near work (reading or working on the computer) wear weaker glasses (approximately +1.25 diopters relative to my most recent prescription) or reading glasses with contacts.

- Whenever I notice blur, practice focusing on things just a little too far outside my easily visible range.

- When outside, use regular prescription, but be sure to keep focus on far away objects whenever possible.

- When possible, rest my eyes.

This is based on the suggested routine from gettingstronger.org, but I have simplified it so that I can state clearly what methods I am employing. This will enable me to better describe exactly the patterns of behavior that led to vision improvement (or lack thereof).

Preliminary data

As a baseline starting point, I am including my prescription as of May 2017. My goal is to continue just getting annual prescriptions, and using that as my official record. I'm hoping to see about a half diopter improvement per year since that was approximately the rate at which my myopia progressed. Of course, that will mean that it'll take 10 years before I can see without glasses, but better late than never.

Fortunately, I was able to convince my optometrist to give me a pair of glasses for working on the computer. I had been wearing reading glasses with contacts anyway so we figured I could just get a prescription with +1.25 diopters added and use that so I wouldn't dry my eyes out with the prescription. In theory, I should switch back to my regular prescription any time I walk away from the computer, but I've effectively started wearing these glasses when I was away from the computer too. I now spend about 70% of my day wearing my -6.25 glasses.

For the first three days with the computer glasses, I had an intense headache and I couldn't see further than my computer screen. It was truly painful, but I persisted, remembering how painful it was when I originally received my erroneous prescription from Warby Parker. I quickly grew accustomed to the changes, and any eye strain was completely unnoticeable after the first week.

I've now been following this program for about a month. As the month has progressed, I have seen an immediate and quite obvious improvement, but I don't want to overstate the results. I feel that this immediate improvement could just be due to my adjustment to this new set of glasses, and my brain getting used to perceiving somewhat fuzzy images better than I was used to before.

To get some early quantitative results, I've tried two different online eye tests to estimate my visual acuity . Both claim that I am 20/20 when wearing my -6.25 lenses. I actually think I'm probably closer to 20/40, based on how well I can see street signs around me (20/40 is worse than 20/20). To put that in perspective, this conversion chart (derived from this paper), suggests that my -1.25 of uncorrected vision should equate to approximately 20/70. Clearly I am seeing better than that even if these tests aren't perfectly accurate. I don't think this is necessarily so dramatic though, and I can't really be sure that this change in visual acuity isn't just a an early effect of my brain getting comfortable with fuzzier images. To really be sure, I will have to wait for my next official eye exam sometime next year. Note, I don't want to measure my vision too often because I believe this could effectively train my eyes to get better at beating Snellen charts, which could bias my results.

A conservative interpretation is that my eyes had the ability to adjust to the sensation of wearing a weaker prescription, and I've been able to compensate for the weaker prescription in a short time by focusing better even in the presence of some blur. I do not expect this rapid improvement to persist in the coming months though. Instead, I am hoping that over the next year or so I will slowly adapt to being able to see further and further with my -6.25 lenses.

I will check back in with an update on my vision at the 6 month point. If I've improved to the point that my -6.25 glasses are truly 20/20 and I have no difficulty viewing things at moderate distance, I may order an even weaker pair of glasses online for computer work.

will stedden

will stedden